History of Architectural Theory & Criticism

SCAD Professor David Gobel

By Walton Stowell 1999

Theories On ‘Orders’ of Classical Architecture

The First Thousand Years of Classical Theories On Architectural Orders

[image 1]

No theories dedicated strictly to architectural ‘Orders’ exist from ancient Greece, despite ancient classical origins being mainly Greek. It was the Greeks who scholars credit with initiating what we call ‘Classical Architecture’, and we certainly have ruins as evidence to remind us in Greece. There are some ancient written references to Greek architecture as well. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato seems to have judged art (and thus perhaps highly styled architecture as well) to be immoral, as Art “misleads the seeker of Truth” and is thrice removed from his ‘metaphysical ideal’. Aristotle disagreed with Plato’s “inappropriate” condemnation of Art (and again we can assume classical styles of architecture). Aristotle said that although the Arts are imitative, “the Arts are instruments of learning” because their representational aspects are “beneficial” for learning basic “philosophical truths”. Aristotle even provided some architectural commentary in his writings about Beauty and Nature in his ‘Poetics of Art’. To Aristotle natural beauty had elements of symmetry, harmony, and definition. Artists learn from Nature, to apply its appealing aspects of beauty to Art.

“The plan of the house, or home, has this and that form; and because it has this and that form, therefore its construction is carried out in manners to achieve the various forms. For the process of evolution (design) is for the sake of the thing (form) finally evolved, and not this for the sake of the process.” – Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

The Roman architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was the author of the earliest intact attempt at writing a complete theory of architectural Orders, at least in publicly known archives. Vitruvius entitled his scrolls ‘De Architectura Libri Decem’ (‘Ten Books On Architecture’). He wrote the scrolls for Augustus Caesar himself, between 33-13 BC. Earlier theory writings only survive in fragments at best, like the Roman ‘Encyclopedias of Marcus Terentius Varro’ which Vitruvius used.

Vitruvius wanted to raise architecture to the level of scientia (scientific knowledge) by demonstrating its Orders to be fundamental to mathematical arts, and thus numerical relationships in design were of key importance to philosophers (lovers of wisdom). Vitruvius stated that architecture must have firmitas (strength), utilitas (utility), and venustas (beauty).

From Vitruvius’s ‘10 Books On Architecture‘:

Firmitas (Strength) – structural statics, construction methods and materials.

Utilitas (Utility) – building types and functional success.

Venustas (Beauty) – aesthetic forms, symmetry, proportions.

For Vitruvius these three qualities of architecture were contained within Greek and Roman (Classical) Orders. The importance of Order to Vitruvius is explained in Book 1, Chapter 2: “I. Architecture depends on Order; arrangement, eurythmy, symmetry, propriety, and economy. II. Order gives due measure to the members of a work considered separately, and symmetrical agreement to the proportions of the whole. It is an adjustment according to quantity. By this I mean the selection of modules from the members of the work itself, and starting from these individual member parts, constructing the whole work to correspond.”

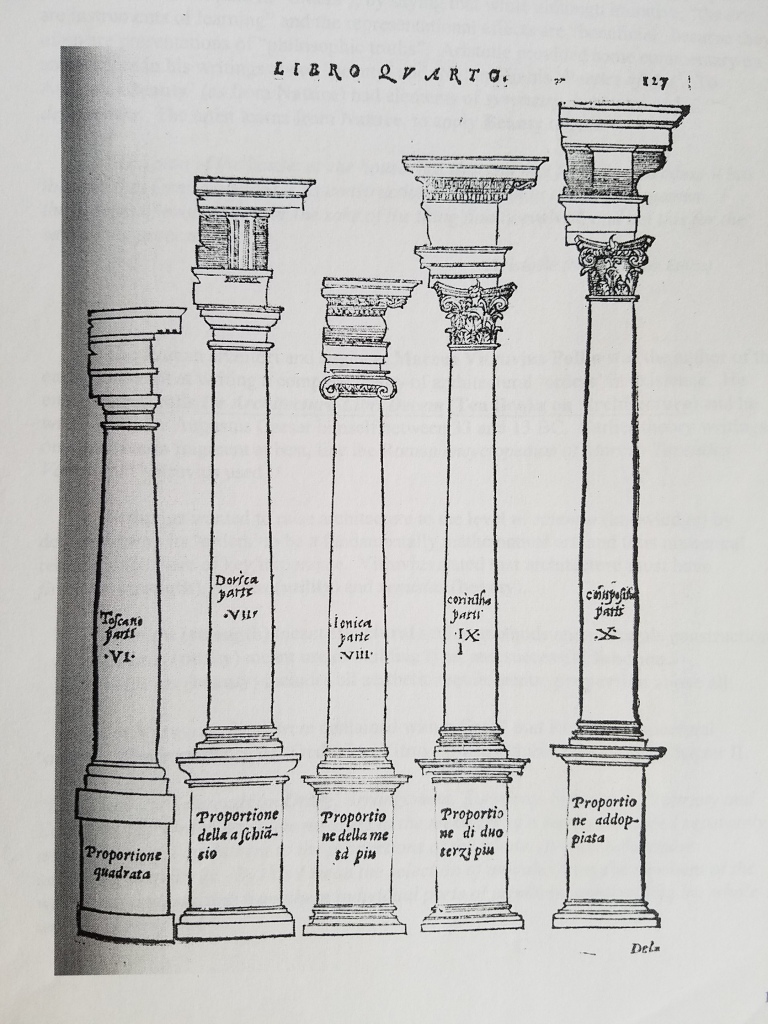

Vitruvius gave examples of Orders from various temples in books 3 and 4. This showed that the Roman Orders of architecture were derived from Greek Orders. To do this he compared Roman column and entablature to the older Greek examples. In Book 3 Vitruvius depicted Ionic and in Book 4 he depicted Doric and Corinthian. Vitruvius also mentioned Attic and Tuscan styles, which made a total of five Orders.

5 Vitruvian Orders of Classical Architecture:

Ionic, Doric, Corinthian, Attic, and Tuscan

To achieve Beauty with ratio compositionis a temple must have proportion: ordinatio, dispositio, eurythmia, symmetria, and proper use of decor and distribution.

Temple Order Beauty Has Compositional Ratios of Proportion:

1. Ordination – synergetic parts work together for a greater unified whole.

2. Disposition – diathesis or division of parts in ordered forms (ideae).

3. Eurythmia – graceful rhythm of elemental arrangements.

4. Symmetry – bilateral balance, harmony of mirrored repetition.

5. Decor – iconography within and around the use of Orders.

6. Distribution – oeconomia or economic member function.

To have Vitruvian architectural proportion, a temple must be laid out using a fixed modulus (little measure), based on the body of the occupant. Protagoras said “Man is the measure of all things” (5th Century BC), and Vitruvius gave us the first ‘modular-man’ theory applied to architectural Orders (1st Century BC).

Vitruvius was never successful in actually producing many buildings (except for his Fano Basilica), but his systematic theory was intended to assure him a safe retirement after serving under emperors Julius and Octavian Augustus. Vitruvius’s influence in antiquity probably remained limited, as we have no popular records of interest in his theory of Orders until Carolingian period records (800s AD).

Isodore of Seville must have known about Vitruvius, while writing his ‘Etymologiae’ in the early 7th Century AD; but only admitted to referencing the Roman ‘Encyclopedias of Marcus Terentius Varro’ (what Vitruvius used, as mentioned earlier). According to what Isodore wrote, there were 5 Classical Orders with the same as names Vitruvius used, but with subtle differences that get into technicalities regarding artistry and archaeology.

Einhard from the court of Charlemagne in the 8th Century AD, taught Vitruvius to his pupils. Ottonian and Byzantine architecture had some Classical influence of course, since those regions had been part of the Roman Empire; but their development out of the Medieval Dark Age reflects their respective regions resulting in Romanesque style. Later Gothic style from the 12th to the 16th Century became even more removed from the Classical Orders. The Medieval period was called ‘The Middles Ages’ by historians who viewed them simply as the time in between the original Classical period, and the Classical Revival period which began in Renaissance Italy.

Leone Battista Alberti was an Italian Renaissance humanist, who wrote a set of 10 books called ‘De Re Aedificatoria’ (‘On The Art of Building’) in 1452. Architect Alberti used Aristotelian and Neo-Platonic philosophy for his aesthetic opinions, but was primarily influenced by Vitruvius. Alberti considered Vitruvius to be worthless as a writer, so for style Alberti studied Cicero.

“… But indeed it is plain from the Book itself, that Vitruvius wrote neither Greek nor Latin, and he might almost as well have never wrote at all, at least with regard to us, since we cannot understand him.” – Alberti

The connection between Alberti’s treatise and Vitruvius is evident in the division of both of their writings into 10 books, the use of historic facts, technical drawings, a preference for past preservation, general terminology of types, and the 5 Orders. Alberti adopted the Roman theory of Orders from Vitruvius, but further inquired into the basic ideas of form. Alberti said that Architecture was the pre-eminenant Art, due to the architect’s definite obligation to society and service to humanity. It was clear to Alberti that Architecture was part of the structure of culture, which brought individuals together socially and contained them in spaces of hierarchy literally as a societies.

“The role of the architect in society is pitched high.” “A building is a kinf of body, in which the lines are produced by the mind, and the materials are obtained from Nature.” – Alberti

For Alberti the relationship between Italian Architecture and Man was inherited from the ancient Greco-Roman world. He believed in developing culture intellectually, and striving for even greater praise as a designer than the “ancients of Classical antiquity”. Despite being a Renaissance man, Alberti was medievally biased against columns; unlike his ancient predecessors. He felt that columns were inferior to walls, due to their structural mass. Walls provide better protection and privacy, and so Alberti’s facades tend to be very flat with no porches.

Alberti addressed public and private buildings in relation to the individuals and their communities. In the second half of his book ‘On The Art of Building’, Alberti dealt with aesthetic topics like beauty and ornament or decoration. He set out an organic theory which regarded the building in terms of the body. Alberti saw beauty as relative, yet rooted in our minds as a neo-platonic archetype. Adornment on buildings is super-imposed, like clothing on our bodies.

Alberti believed proportions to be immutable, like the laws of Nature and the body; using even and odd numbers where appropriate (one central mouth, two eyes… all symmetrical). In Aristotelian tradition, Alberti thought that by observation and imitation of Nature one could apply harmony (concinnitas) to architecture. To Alberti architecture was analogous to the infinite multiplicity of phenomena in Nature; and that was reflected in the different Orders of architecture. Thus he said Doric was strength and duration (masculine), Corinthian was taper and beauty (feminine), and Ionic was in between (hermes). Alberti was the first to recognize the Composite order, which he called ‘genus italicum’. Only after writing his book, did Alberti practice architecture by designing buildings. While his design work was limited, Alberti made a most significant contribution to architectural literature.

Il Filarete (The Friend of Virtue) aka Antonio Avertino was another Italian Renaissance Florentine, was hired under Duke Sforza of Milan (like Leonardo Da Vince) when he wrote his treatise in 1464. This proportions of the Orders were a reversal of Vitruvius’s specifications, because he wanted to express a Christian message. Filarete thought that temple proportions of Antiquity were squat, and the Christian churches attempt to elevate the human soul closer to God, by building higher with greater verticality. Also he stressed the building as an organism (that even gets sick).

Francesco di Giorgio Martini wrote ‘Uomo Universale’ in the late 15th Century. It was a synthesis of Alberti and Filarete. Martini’s book had an underlying anthropocentric message that “all architectural measures and proportions are derived from the human body.” Martini included the cosmos with man and architecture for the first time, saying that man has within himself a microcosm, which contains “all the general perfections of the world”.

Donato Bramante seems to have made the greatest significant achievement during the Quattrocento (15th Century) to Classical architecture, with his exquisitely beautiful built designs. Bramante was an expert in perspective and proportion. La Tempietto in Rome is a brilliant example of evolution of the Italian revival of Classical Orders that Alberti began.

Cesare Cesariano was a pupil of Bramante, and wrote a Vitruvian treatise with the excellent addition of illustrations that directly related to the text. Cesariano made no contributions to the historical understanding of Vitruvius, however he did provide us with his own excellent versions of the Orders. In his writings, Cesariano did say that Vitruvius’s Orders were still relevant for new buildings of the time (16th Century).

In subsequent decades the Vitruvius editions made by Fra Giocondo (1511) and Cesariano (1521) were plagiarized and republished under other names. In 1531 the architect Antonio da Sangallo (the younger) was frustrated at the inadequacy of existing editions of Vitruvius, so he planned a new translation to investigate older sources, and check the statements of Vitruvius against the actual ruins of the ancient buildings he wrote about. Sangallo’s writings are notoriously missing to this day.

The Neo-Classical rigid proportional system of column Orders was first published by Sebastiano Serlio in the 16th Century. Serlio based his writings explicitly on Vitruvius’s prescriptions of propriety for the Orders. Serlio stipulates that “these modern times” need to adjust the forms to “our Christian customs”. I suppose he meant that Neo-Classical architecture was meant to respect churches and the Catholic Church.

In his book ‘Libro Extra-Ordinario’ Serlio founded a tradtion, codified in innumerable 16th Century books on Orders, reducing architectural theory to instructions on how to use the Orders. It is these limitations on form that make Neo-Classical architecture so great, and a memorial to classical theory. Classical Revival styles continued through the Victorian period, and are still strong today.

*

Bibliography

[image 2]

Gobel, David – from his SCAD class ‘The History of Architectural Theory & Criticism’, 1999; “The word ‘theory’ is from the Greek theorea (theater), and theomomi which is to look at a thing, site, or spectacle. Criticism is a cutting moral judgment. Theory is very important; men like Aristotle gave us something to talk about.”

Kruft, Hanno-Walter – ‘A History of Architectural Theory, From Vitruvius To The Present’, c.1994, Princeton Architectural Press, Chpt 1-6.

“This pioneering critical survey of the most significant European and North American statements of architectural theory will be welcomed for its cohesive approach to a subject of huge scope. Architectural theory is defined as ‘any architectural system expressed in written form, based on aesthetic criteria’. Professor Kruft’s exposition on theorists is grounded in his reading of primary texts, which embrace treatises such as those of Vitruvius and Italian Renaissance writers.” – Neue Zurcher Zeitung

Vitruvius, Marcus Pollio – ‘Ten Books On Architecture’, Trans. Morgan, Dover Inc. NY 1960, 1914. “Thus a third architectural order… was produced out of the other two orders… For Dorus the son of Hellen and the nymph Phthia, was King of Achaea and he built a fane of this order, in the precinct of Juno at Argolis, and others of Doric order in other cities of Achaea, although the rules of symmetry were not yet in existence.” – Vitruvius

**